A Streak of Lavender: Queer Spaces and the History of Lavender

Laura B. Henry, HIV Alliance Queer Resource Center Manager

The color lavender has long been associated with the queer community at large. From the “lavender marriages” of early 20th century Hollywood, to our very own Lavender Graduation at the University of Oregon, this floral moniker has designated LGBTQ+ spaces and communities for hundreds of years.

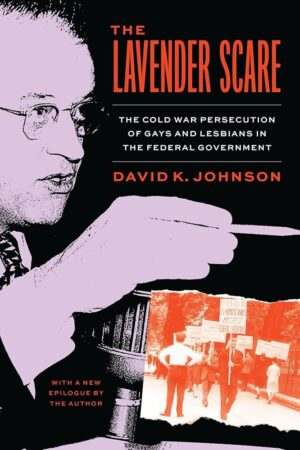

First coined by David K. Johnson in the title of his 2004 book “The Lavender Scare: The Cold War Persecution of Gays and Lesbians in the Federal Government”, the Lavender

Scare was a moral panic and witch hunt spurred by the anti-communist “Red Scare” and perpetrated by members of the United States government in the early 1950’s. Its goal was to root out, disgrace, and dismiss any “lavender lads” (a term used by Senator Everett Dirksen) working for the US State Department. The hunt soon expanded beyond just the State Department, to include all federal employees and members of the military.

Helen Grace James was an Airman Second Class in the US Air Force in 1955 when she was investigated for her sexuality as part of this expanding Lavender Scare and summarily discharged as “undesirable”.

After her discharge, Helen felt alienated. “I had to move myself away. I couldn’t be around my family and friends,” she said.

Many queer people struggle to find places of community, to feel accepted, and to shirk the shame put on them by unfair practices. Though Helen returned to a California where gay bars could legally operate after her discharge, she still struggled to prove herself throughout the rest of her life.

“I couldn’t be in the same area with that shame. I went to Stanford, I was a professor at Cal Fresno. I had patients, friends, students I learned so much from. I’ve done this all because I’ve been pushed. I need to do as much as I can to prove I’m a good person.”

In 2018, at age 90, Helen filed a lawsuit against the US Airforce and won the upgrade of her discharge to “honorable” status.

At the start of the Lavender Scare in Washington, DC, “there was a developing vibrant community based culture in bars, in parks, in parties,” said Marc Stein, a History Professor at San Francisco State University in a 2024 PBS NewsHour Interview. “One could have a relatively full and interesting and dynamic private life.”

Though legal, gay bars in California were still frequent targets of harassment from police. This harassment as well as cultural disdain led to divisions within the community, with some gay bars shunning more flamboyant presenting clientele. One bar operator even said “I do not welcome this type in the bar. I am rude to them, watch them closely for any infraction of my arbitrary rules, and they soon leave.”

Before the lavender lads of the 1950s, by the late 1940’s newspapers used the “lavender set” as shorthand for groups of gay men. And even as Lavender Scare progressed, some resisted the dismissive appropriation of lavender and used the term positively within their own communities.The Lavender Brotherhood, a term dubbed by author Dorothy Dean in 1956, described a loosely formed group of mostly white gay men that the author admired. The same author later published a newsletter called “All-Lavender Cinema Courier” in the mid 1970’s.

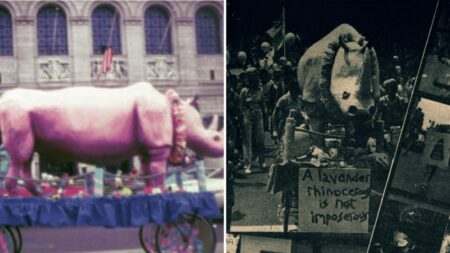

The reclamation of lavender by the community became stronger in 1969, when, after the Stonewall Riots, a gay power demonstration formed a “purple column” of protesters wearing lavender ribbons and marching under a lavender banner. The color continued to appear in queer culture throughout the 1970’s from activist groups like the Lavender Panthers who patrolled San Francisco led by an armed preacher to the surprising appearance of a giant lavender rhinoceros at Boston’s pride parade.

Taking a cue from Victor Hugo Green’s “Green Book”, a travel guide for Black Americans published from 1933-1966, members of the LGBTQ+ community began publishing travel guides of their own. In 1963, Guy Strait published the first edition of “The Lavender Baedeker”, a gay focused travel guide, as an extension of his already popular San Francisco newspaper “Citizen’s Guide”. In this inaugural edition, both Portland and Eugene, Oregon, had listings including spaces such as The Harbor, in Portland, and Room 13 Lounge, in Eugene.

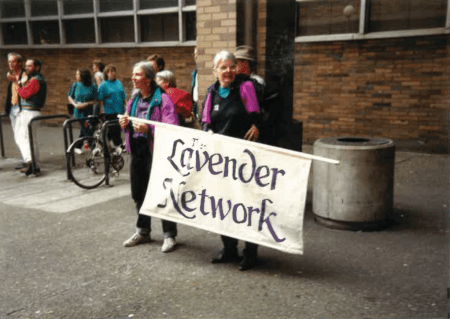

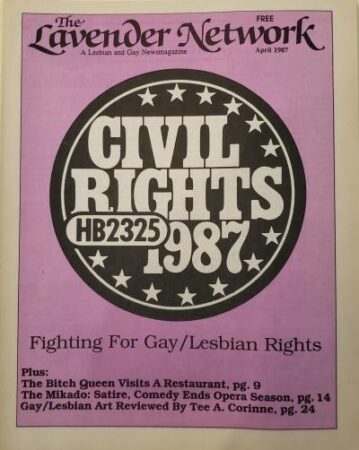

Beyond queer spaces, the history of lavender expanded into queer news magazines locally in 1986 with the first publication of The Lavender Network. The newsmagazine was published in Eugene, Oregon monthly between 1986 and 1994.

The newsmagazine described itself as follows: “Our purpose is to build community unity through networking, and to work toward social change. We believe that strength comes from unity. By recognizing and respecting our diversity while emphasizing our similarities and shared interests, TLN can help facilitate accord and trust-building within the community. TLN encourages lesbian and gay pride and dignity through positive exploration of our gay cultural heritage. We also provide current community news, health education and AIDS information, a community resource guide and a calendar of community events. TLN is committed to human rights, lesbian and gay empowerment, disarming homophobia and ending discrimination.”

Early issues of the newsmagazine focused heavily on the impact of the HIV/AIDS epidemic on the LGBTQ+ community, including publishing obituaries and memorials of those taken by the virus or related illnesses. They used their platform to inform Eugene and surrounding areas of federal updates regarding drug research, testing, education, and support groups.

In 1939 Carl Sandburg published a multi-volume biography of Abraham Lincoln, and in so writing, described Lincoln’s early male friendships as containing “a streak of lavender, and spots soft as May violets”. While hateful groups seized these terms to be used in derision against the queer people of the 1940s, the beauty of the phrase is unmistakable. A streak of lavender, a beautiful part of a whole being, a spot of color and brightness and joy.

With the spirit and strength of our history behind us, and the power of community and physical spaces, HIV Alliance would like to announce our involvement in the collaborative project The Lavender Network. Named with the permission and blessing of the 1986 newsmagazine’s publishers, The Lavender Network is an expansion and development of Transponder and HIV Alliance’s current Queer Resource Center at 1185 Arthur. The expanded collaboration between Transponder, Queer Eugene, Eugene Pride, Eugene Performing Arts Center, and HIV Alliance has been relocated to 440 Maxwell Road in Eugene, and will begin providing services Monday November 4th, 2024.

All of the current Queer Resource Center services including Harm Reduction Services, PrEP Navigation, Sylvia’s Closet (Gender Affirming Products), Peer Support Services, Support/Community Groups and the Food Program will be provided at the new Lavender Network location on Maxwell, as well as additional services and events provided by our new collaborators.

We look forward to welcoming you to The Lavender Network soon!

References:

Interview with David K. Johnson, author of The Lavender Scare: The Cold War Persecution of Gays and Lesbians in the Federal Government

The Air Force expelled her in 1955 for being a lesbian. Now, at 90, she’s getting an honorable discharge. – The Washington Post

Travel Guides 1949-1969 — The Umbrella Project

The Gay Bars and Vice Squads of 1950’s Los Angeles

How the Lavender Scare forced LGBTQ workers out of the federal government

Violet delights: A queer history of purple

How lavender became a symbol of LGBTQ resistance | CNN

The Negro Motorist Green Book – Wikipedia

OSQA Collection ~ The Lavender Network Newsmagazine

Friends of Dorothy Dean | The New Yorker

How A Lavender Rhino Became A Symbol Of Gay Resistance In ’70s Boston | WBUR News