HIV’s Queer History and the Future of Treatment and Prevention

Laura B. Henry, HIV Alliance Queer Resource Center Manager

During an October 1982 White House press briefing journalist Lester Kinsolving questioned Larry Speakes, President Ronald Reagan’s press secretary, about the president’s reaction to AIDS, mentioning the disease was known as the “gay plague”.

The press pool erupted in laughter.

“I don’t have it,” Speakes said, ignoring the question and causing more laughter in reaction. Speakes followed up by asking Kinsolving multiple times if he had AIDS.

First described in 1981 as GRID (gay-related immune deficiency), by the autumn of 1982 the CDC had changed the name to AIDS. Despite the growing cases and a new name, news outlets struggled with the disease, or at least how to cover it—some even shied away from giving it too much attention. Though the New York Times initially reported on the mysterious illnesses in July 1981, it would take almost two years before the prestigious paper gave AIDS front-page space on May 25, 1983. By that time, almost 600 people had died from it.

By the end of 1984, AIDS had already ravaged the United States for a few years, affecting at least 7,700 people and killing more than 3,500. Scientists had identified the cause of AIDS—HIV—and the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) identified all of its major transmission routes.

HIV (human immunodeficiency virus) is a virus that attacks cells that help the body fight infection, making a person more vulnerable to other infections and diseases. It is spread by contact with certain bodily fluids of a person with HIV, most commonly during unprotected sex, or through sharing injection drug equipment. If left untreated, HIV can lead to AIDS (acquired immunodeficiency syndrome).

Despite knowing this, U.S. leaders of the time had remained largely silent and unresponsive to the health emergency. It wasn’t until September 1985, four years after the crisis began, that President Ronald Reagan first publicly mentioned AIDS.

From 1981 to 2018, 10,566 Oregon residents were diagnosed with HIV infection and 4,613 Oregon residents with HIV died.

In 1983, two years after the start of the AIDS crisis, the FDA banned men who have sex with men from donating blood in an effort to keep HIV out of America’s blood supply. Without any viable treatments for HIV, patients were often anemic, requiring blood transfusions frequently. This increased transfusion burden led to a critical shortage of available blood for US hospitals.

Seeing this crisis compounding the already horrendous situation facing people living with HIV, the San Diego Blood Sisters, a group of lesbians from the Women’s Caucus of the San Diego Democratic Club, began organizing blood drives. In their nine years as an organization, the San Diego Blood Sisters organized twelve blood drives. Despite facing backlash from the public, fearing that any queer organizing of blood donation would taint the blood, the organization continued and inspired similar groups as well as increased lesbian activism on behalf of their gay brothers. The FDA would not revise its guidance regarding the deferral of donations from gay and bisexual men until May, 2023.

In 1985, the first test to detect HIV (ELISA) was licensed. Though treatments for the virus had yet to be developed.

In 1985, the first test to detect HIV (ELISA) was licensed. Though treatments for the virus had yet to be developed.

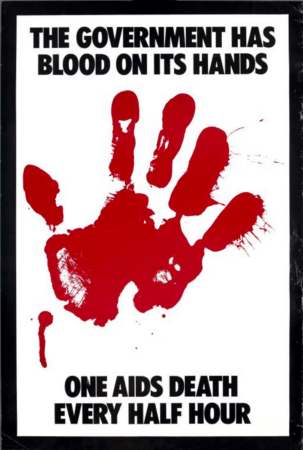

In October 1988, 1,500 protesters marched outside the headquarters of the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in Rockville, Maryland.

“The government has blood on its hands; one AIDS death every half hour.” The marchers chanted. “Fifty-two will die today/ Seize control of the FDA!”

The protesters themselves were a mixture of HIV/AIDS patients, friends, and queer activists from across the country. This was the first national action of the activist group ACT UP (AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power), and they protested what they saw as the failure of the FDA to approve HIV treatment medications in development. By October 1988, more than 45,000 Americans had died from HIV/AIDS related illnesses.

“I didn’t think I was going to survive five years beyond that moment,” Peter Staley, an AIDS patient at the protest, told The Guardian in 2023. “Small groups of people, as long as they have a lot of determination and are highly strategic, can create change and create change pretty quickly depending on the issue. It is worth noting that the FDA caved to almost all of our demands within nine months, within a year after that demonstration.”

The FDA’s newly implemented changes included a new rule promising faster development of AIDS drugs and wider access to drugs in the clinical trial process, even for patients outside the trial itself.

In March 1987, AZT became the first drug to gain approval from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for treating AIDS, though the cost was prohibitively high, at more than $8,000/year (nearly $22,000/yr in today’s money). In the early 1990s, additional drugs in the same class as AZT gained FDA approval. The development of AZT and others showed that treating HIV was possible, and these drugs paved the way for discovery and development of new generations of antiretroviral drugs.

Throughout the remainder of the 1990’s, more antiretroviral drugs, and combinations of drugs, were developed and prescribed to those living with HIV/AIDS, and in 1992 the first rapid test for HIV was released. Through earlier detection, raising awareness of HIV status, and linkage to care and treatment, testing still plays an important role in addressing HIV.

Among the 1.2 million people with HIV in the U.S., an estimated 13% do not know they are living with HIV and this share accounts for nearly 40% of new transmissions. Awareness of HIV status allows those who are positive to engage in HIV treatment which optimizes health outcomes, reduces the amount of virus in the body and prevents transmission. Additionally, studies show that those who learn they are living with HIV modify their behavior to reduce the risk of HIV transmission.

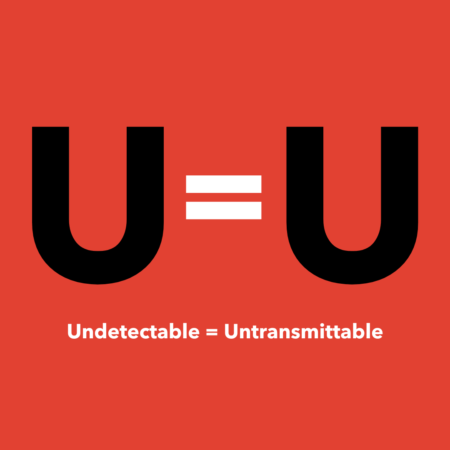

In 2016 the Prevention Access Campaign (PAC) launched the HIV awareness campaign U=U, or Undetectable equals Untransmittable. Per End HIV Oregon, “U=U means that people living with HIV who take their medication as prescribed and maintain an undetectable viral load cannot transmit HIV to others through sex. This is a liberating new reality for those living with HIV and their sex partners. U=U means more sexual freedom and reduces stigmas associated with HIV.”

In 2016 the Prevention Access Campaign (PAC) launched the HIV awareness campaign U=U, or Undetectable equals Untransmittable. Per End HIV Oregon, “U=U means that people living with HIV who take their medication as prescribed and maintain an undetectable viral load cannot transmit HIV to others through sex. This is a liberating new reality for those living with HIV and their sex partners. U=U means more sexual freedom and reduces stigmas associated with HIV.”

Despite available treatments, the community still faced anxiety over unprotected sex without an approved HIV prevention method. Condom use was necessary but not a foolproof method. Nearly 30 years after the first antiretroviral treatment, the FDA approved the first oral PrEP (Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis) medication, Truvada, in 2012. Two years later, the CDC recommended PrEP for high-risk groups, including gay and trans individuals. In 2014, the FDA approved a second PrEP medication, Descovy. PrEP is taken to prevent getting HIV and is highly effective for preventing HIV when taken as prescribed. PrEP reduces the risk of getting HIV from sex by about 99% and reduces the risk of getting HIV from injection drug use by at least 74%.

A trailblazer in PrEP research, Dr. Dawn K. Smith played a key role in ensuring people could use and access PrEP. Leading the first safety study on PrEP at the CDC, and helping to create guidelines for doctors on how to use it, Dr. Smith also led a major study examining how PrEP was prescribed and used in community health centers.

The future is bright for the treatment and prevention of HIV, with the July 2024 news that a seventh patient has been cured of HIV via stem-cell transplant. Of course, this process is not something that is currently viable on the large scale, and is too dangerous for healthy people living with HIV to consider. Research into a vaccine for HIV is also ongoing, though challenging because of the quick mutation rate of the virus, and multiple research facilities are conducting preclinical trials for potential vaccines that would be effective against a wide range of HIV strains.

The future is bright for the treatment and prevention of HIV, with the July 2024 news that a seventh patient has been cured of HIV via stem-cell transplant. Of course, this process is not something that is currently viable on the large scale, and is too dangerous for healthy people living with HIV to consider. Research into a vaccine for HIV is also ongoing, though challenging because of the quick mutation rate of the virus, and multiple research facilities are conducting preclinical trials for potential vaccines that would be effective against a wide range of HIV strains.

HIV Alliance provides free and confidential HIV, Syphilis, and Hepatitis C testing at our Queer Resource Center, currently located at 1185 Arthur Street in Eugene. The Queer Resource Center will be moving and becoming The Lavender Network, in collaboration with Transponder, Eugene Pride, Queer Eugene, and Eugene Performing Arts Center to 440 Maxwell Rd. in Eugene, November 2024. HIV Alliance also offers PrEP navigation, as well as HIV Care Coordination at multiple locations across Oregon.

References:

HIV infection in Oregon

What Are HIV and AIDS?

How AIDS Remained an Unspoken—But Deadly—Epidemic for Years | HISTORY

Our History – HIV Alliance

‘The start of the national Aids movement’: Act Up’s defining moment in queer protest history | Aids and HIV | The Guardian

“The AIDS Epidemic in the United States, 1981-early 1990s” | The CDC

Lesbian AIDS Activism

Lesbian Solidarity During the AIDS Epidemic – YouthCO

End HIV Oregon

End HIV Oregon Annual Progress Report 2023

Tracing the Path of PrEP: A Brief History of HIV Prevention

New HIV Treatments on the Horizon

HIV: how close are we to a vaccine — or a cure?

Advancing toward a preventative HIV vaccine – IAVI